The unique trees of Yakushima

“When you destroy the forests you upset the balance of nature. The present generation must remember that it only holds the forests in trust for future generations”

These are the words of the English botanist and plant hunter, EH Wilson, who arrived on the remote island of Yakushima in February 1914. Yakushima is about 50 miles off the coast of Kyushu, the southernmost of the four islands that make up the Japanese archipelago. His mission was to see the giant ancient wild Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) he had heard grew there. He stayed just 10 days, yet his visit had momentous consequences.

I too had a long-held desire to visit Yakushima, after learning that it was home to Japan’s oldest cedar. The Jōmon Sugi is estimated to be anywhere between 3,000 and 7,200 years old. It has a diameter of 5.2 metres and stands at an altitude of 1,300 metres, on the slopes of the highest peak of this volcanic island that rises steeply from the surrounding sea. It’s a 10-hour trek to get there and back.

Image 1: Wilson Stump

There are dozens of ‘Yakusugi’ on Yakushima—cedars over 1,000 years old. It’s a small, circular island, almost entirely forested, no more than 40-50 kilometres across with a unique microclimate, from sub-tropical to Northern temperate. Much of this mountainous landscape, with its deep ravines, roaring torrents and steep, rocky inclines covered in dense forest, is still difficult to access.

That did not stop the Shimadzu clan, landowners during the Edo Period (1603-1868), from cutting down 70% of the Yakusugi to make roof shingles. It then became a national reserve. After a forestry railroad was built in 1923, logging resumed until the 1960s. Half a century earlier, Wilson had urged the Japanese authorities to preserve Yakushima’s extraordinary ecosystem; he declared that it had the most remarkable forests in Japan, and was richer in vegetation than anything he had seen, even in his extensive exploration of China.

Yet although the forests have regrown and there are plenty of ancient cedars, hemlock, hinoki and other, broad-leaved trees to be seen, the relics of Edo-period logging are still present. Many huge tree-stumps remain, slowly rotting hulks, in many cases hundreds of years old. The most famous of these is the Wilson Stump—hollow, 15 metres round, felled at the end of the 16th century to build a temple in Kyoto. [Image 1]

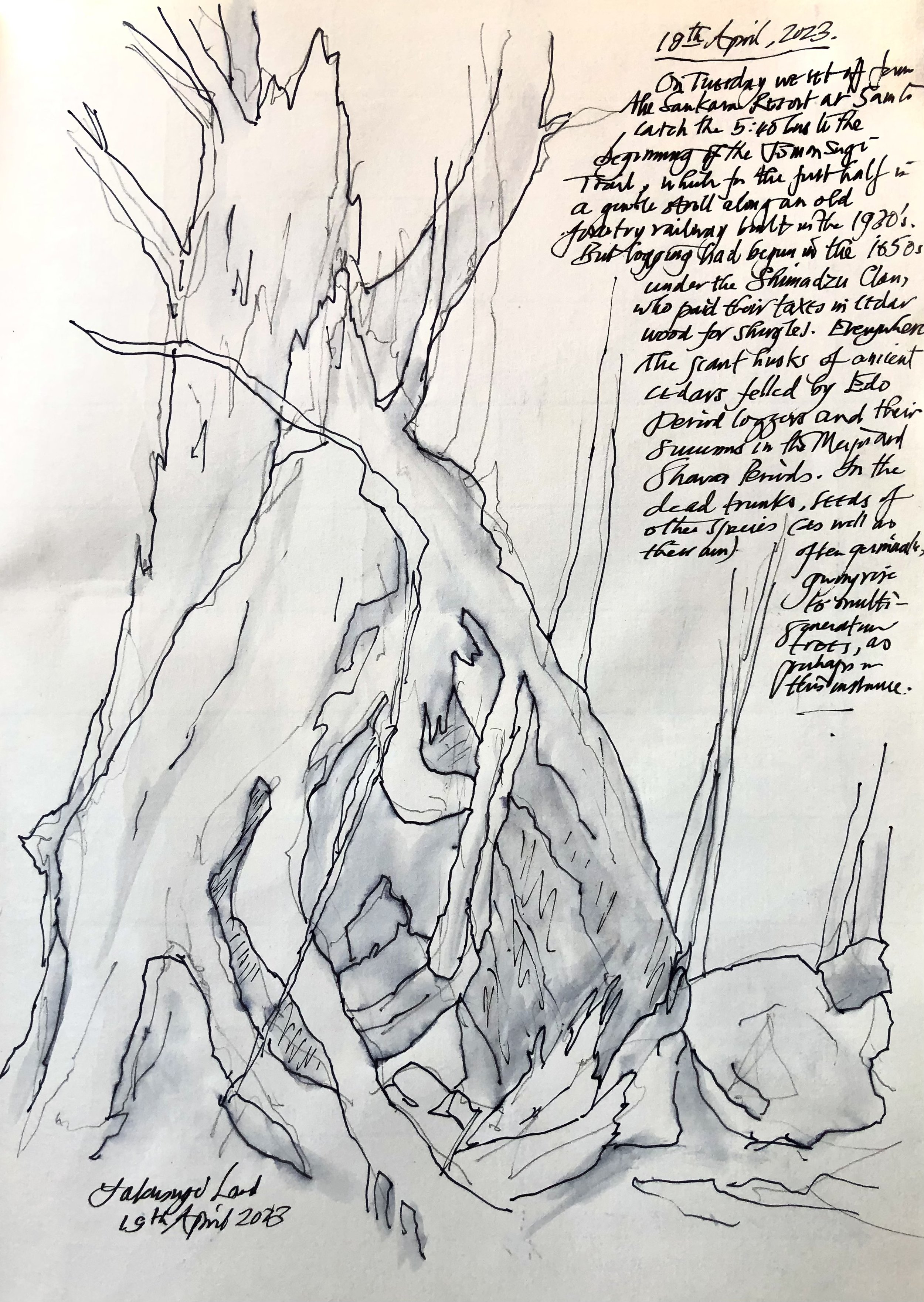

These trees were cut at 3-4 metres up, leaving a platform on which fresh seedlings would eventually take root, giving the appearance of regrowth. Here you can see mighty second- or even third-generation cedars (and often other species) coalescing with these brooding relics, their resin-rich timber preserved for centuries under a mantle of velvet moss— vast, spreading, gothic forms in the primeval forest. [Image 3 and 3a]

Image 4: Drawing of Buddhasugi

With such high rainfall, fog-bound upper slopes and thin soils on a granite base, the cedars add growth rings at an infinitesimal rate, but can reach 5-6 times the normal lifespan of 500 years; hence their massive girth and heights of 30-40 metres, even with the storm-broken tops of the most venerable specimens. The oldest, such as the Buddhasugi [Image 4] or the Kigensugi [Image 5 and 5a] have dozens of epiphytes growing on them. You can tell a Yakusugi, as its bark has turned grey and gnarled, losing the reddish-brown strips of it youthful centuries.

It’s no surprise that Yakushima’s damp, tangled interior was the inspiration behind arcadian scenes in Studio Ghibli anime film Princess Mononoke (1997): moss-clad roots and boulders, log bridges, titanic cedars and tsugi (hemlock) rising like sentinels above the forest canopy. As you walk through the island’s forests you can understand why the early islanders believed these mountains to be the domain of the gods.

Not long before logging finally stopped, the Japanese invented a 20kg, 2-metre long chainsaw, capable of taking down a giant cedar in well under an hour—a far cry from the handsaws of old [Image 6]. We should salute the forest rangers and botanists who kept Wilson’s legacy alive and successfully campaigned to save the island’s unique environment and its Yakusugi.

Image 6: Drawing of Japanese handsaws

In the end, we did not meet the Jōmon Sugi. Two-thirds of the way, my wife slipped and dislocated her shoulder. Far from any road and with no mobile reception, we had to clamber and walk very slowly back down to base. An agonising five-hour trek, a bus and car journey, and finally the only hospital on the island.

But as the sun-dappled light filtered through the sacred groves, past the numinous dark silhouettes of long-dead trees, we were thankful for the deep consolations of the natural world ... and for the pioneering work of EH Wilson.

Source: Tomoko Furui, Wilson’s Yakushima Memories of the Past (Yakushima: KTC Chuo Shuppan, 2013)Donate to plant trees

Together we can create real change by planting trees and restoring the natural beauty of our planet.